User:TwoScars/sandbox

| Formerly | Bakewell & Ensell Benjamin Bakewell & Co. Bakewell, Page & Bakewell Bakewell, Page & Bakewells Bakewells & Anderson Bakewells & Co. Bakewell & Pears |

|---|---|

| Company type | Private company |

| Industry | Glassware |

| Founded | 1808 |

| Founder | Benjamin Bakewell, Benjamin Page, Edward Ensell |

| Defunct | 1882 |

| Fate | closed and factory site sold |

| Headquarters | Water and Grant streets (1808-1854); Bingham Street (1854-1888), Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania |

Key people | Benjamin Bakewell, Thomas Bakewell, John Palmer Pears |

| Products | blown and pressed glassware, including lead crystal with cutting and engraving |

| Revenue | $45,000 (1825)(equivalent to $1,211,824 in 2023) |

Number of employees | 73 (1825) |

Bakewell, Pears and Company was Pittsburgh's best known glass manufacturer. The company was most famous for its lead crystal glass, which was often decorated by cutting or engraving. It also made window glass, bottles, and lamps. The company was one of the first American glass manufacturers to produce glass using mechanical pressing. In the 1820s and 1830s, Bakewell glassware was purchased for the White House by presidents James Monroe and Andrew Jackson. Founder Benjamin Bakewell is considered by some to be father of the crystal glassware business in the United States.

The company was founded in 1808 by Benjamin Bakewell, Benjamin Page, Robert Kinder and Company represented by Thomas Kinder, and Edward Ensell. The original company name was Bakewell and Ensell, and the the factory was called the Pittsburgh Glass Manufactory. The company had nine different names through its lifetime, which typically changed when principals in the partnership changed. The name Bakewell was used in all nine names. Bakewell family members, as well as members of the Page and Pears families were also involved with the company. The name Bakewell, Pears and Company was used for the longest period, 1844 through 1880. The glass works was closed in 1882, and the facility was sold to a wire manufacturer.

Pittsburgh became the nation's glassmaking center in the 1850s. Its location provided access to river transportation, coal for fuel, and good quality sand. English businessman Benjamin Bakewell recruited skilled English glassworkers that enabled the company to become well known for its glass cutting and engraving. Some of the company's local workers became skilled enough to start their own glass companies. Among those glass men were John Adams (Adams & Company), Thomas Bakewell Atterbury (Atterbury & Company), James Bryce (Bryce Brothers), David Challinor (Challinor Taylor), and William McCully (McCully and Company).

Background[edit]

Benjamin Bakewell moved to New York from London in 1793. In London he had been an importer of luxury goods, and he started the same type of business in his new home city.[1] Living with Bakewell's family was his wife's widowed sister and her daughter Sarah Palmer. Sarah Palmer became romantically involved with a young English clerk in Bakewell's firm named Thomas Pears, and they married in 1806.[2][Note 1] Bakewell was very familiar with French and English fashions and styles.[4] His import business prospered, and he diversified by establishing a brewery in New Haven, Connecticut.[5] The brewery business did not do well, and was destroyed by fire in 1803 and not rebuilt.[6] The import business thrived enough that by 1807, Bakewell owned multiple houses and stores in New York—plus land in Vermont, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.[7] Among those assisting him in his New York import business was Thomas Woodhouse Bakewell, son of Benjamin's brother William. Benjamin's own son, also named Thomas, also became involved in the business.[8][Note 2]

The Napoleonic Wars eventually ruined Bakewell's import business. Because of war between France and Great Britain, American ships' cargoes and crews were always under the threat of being confiscated by those two naval powers. In November 1806 Great Britain enacted a blockade of the European continent. Napoleon responded by issuing the Berlin Decree that blockaded Great Britain. The United States responded by legislating the Embargo Act of 1807, which said that United States vessels could not sail to foreign ports. This ruined Bakewell's import business, and he was bankrupt by January 1808.[9] After losing everything except his clothing, furniture, and personal library, Bakewell was eager to leave New York.[10] Businessman Benjamin Page lived on the same street as Bakewell. He also lost money because of the Embargo Act, but his losses were not as severe as Bakewell's. Page closed his importing business in 1808, and sought better places to invest his money.[11]

Beginning[edit]

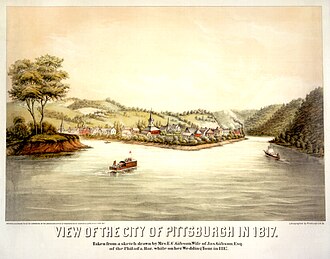

In 1807 George Robinson and Edward Ensell began building a glass works in Pittsburgh. The town would have a population of 4,700 by 1810, with over 200 brick houses plus over 350 wooden structures.[12] Pittsburgh had a transportation advantage for glassmaking because it was located where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers converge to form the Ohio River.[13] Coal that could be used as fuel for manufacturing was available nearby.[14] Robinson and Ensell depleted their funding before construction was completed, so the incomplete works was sold in 1808 to New York merchants Benjamin Bakewell, Benjamin Page, and Robert Kinder and Company represented by Thomas Kinder.[15]

The glass works was located along the Monongahela River at the foot of Grant Street extending from the south side of Water Street to the river.[16] This gave the facility easy access to the town and to river transportation.[17] The new company was known as Bakewell and Ensell, and consisted of Bakewell, Page, Ensell, and Robert Kinder and Company.[18] Bakewell moved to Pittsburgh and provided the business expertise for the company, while Page and Kinder remained living on the nation's east coast. Page moved to Pittsburgh in 1814.[11] Ensell provided the glassmaking expertise, which included the processes for making window glass and flint glass (leaded crystal).[19] Operations began by August 1808.[17][Note 3]

Based on his experience with importing quality goods, Bakewell believed there was a market for high quality glassware. He was already aware of the designs that were popular in Europe.[4] He would not become the first producer of crystal glassware in the United States. That had already happened in the previous century, before the United States existed, at a short–lived works owned by Henry William Stiegel.[4] During the early 1800s in the United States, the production of crystal (a.k.a. flint) glass was limited by a lack of skilled workers and the scarcity of a necessary additive known as red lead.[21] Much of the crystal available in the United States during the early 1800s was imported from England, and Bakewell employed English and French craftsmen to compete in that market.[4]

Benjamin Bakewell and Company[edit]

Ensell and the other three partners did not get along. The Bakewell family believed Ensell misrepresented his qualifications.[22] Ensell left the company in 1809 after only six months.[23] One historian doubts that Ensell had faulty glassmaking expertise, since Bakewell lost a lawsuit against Ensell in June of the same year—and Ensell started another glass factory in 1810.[24] Bakewell and the two other remaining principals continued the company.[23] The firm was renamed Benjamin Bakewell and Company.[23][Note 4] Bakewell's company called its glass works the Pittsburgh Flint Glass Manufactory.[26] The factory's original furnace contained only six pots.[27][Note 5] Changes were necessary at the glass works because of a number of problems. The furnace for melting glass was not well constructed. The work force was not highly skilled, and it was reluctant to train new employees (or management). Some of the raw materials used to make glass were delivered by wagon from Philadelphia and New Jersey—a considerable distance for the time that was difficult to travel because the Allegheny Mountains had to be crossed. Sand, a major raw material for glass, was obtained from near Pittsburgh—but it was low-quality and more suited for window or bottle glass than glassware.[30]

Bakewell learned the glass business and worked to solve his factory's problems. The furnace was replaced with a ten-pot version in 1810.[27] Better raw material sources were found, and Bakewell was able to produce better quality glass.[31] The company's products were mostly glassware, including tumblers, wine glasses, jars, and egg cups. Flint glass versions of these products could be made because Bakewell was able to make his own red lead using Mississippi pig lead.[32] Among the new hires in 1810 was former factory superintendent and glass cutter William Peter Eichbaum, who cut the first crystal chandelier made in America. The chandelier was sold by Bakewell to an innkeeper for $300 (equivalent to $5,844 in 2023).[33]

Bakewell's son Thomas became a valued assistant and expert chemist.[34] Although many European countries forbid their glassworkers to come to the United States as part of an effort to retain glassmaking secrets, Bakewell improved his workforce by smuggling skilled glass workers from England to Pittsburgh.[35] Bakewell's glass works began to establish a reputation for "quality and workmanship".[17] Effective March 13, 1811, the company's partnership was dissolved, and it was announced that the "business will in future be carried on by B. Page and B. Bakewell, under the firm of the former partnership."[36] Robert Kinder and Company withdrew from the partnership because it was having financial difficulties. Associates of Page, and Bakewell's brother William, made sure the partnership continued.[37]

Effects of war[edit]

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Napoleonic Wars and resulting tariffs had already made trade with Britain and France difficult. The War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain was good and bad for American glassmakers. England, part of Great Britain, controlled the supply of a necessary raw material for crystal—red lead. It also controlled the supply of good quality sand. The Embargo Act of 1807, and then the War of 1812, made it nearly impossible for American companies to acquire the raw materials necessary to produce good quality crystal.[14] However, the lack of European goods also meant that consumers in the United States became dependent on domestic producers for manufactured products. The number of glass factories in the United States increased from 22 in 1810 to 44 in 1815.[38] Many of these factories produced window glass or bottles, which did not require red lead or high quality sand.[39]

In the case of Benjamin Bakewell and Company, domestic sources of red lead and good sand had been discovered.[Note 6] Management at Bakewell realized that they had an opportunity to take advantage of an increased demand for glass, and the company prospered beyond expectations.[38] Bakewell's oldest son Thomas formally joined the company on September 1, 1813. Although Thomas Bakewell was a salaried employee and not a shareholding partner, the company changed its name to Bakewell, Page and Bakewell. At that time Page began plans to move to Pittsburgh, and he arrived with his family in 1814.[38] In 1814 another ten-pot furnace was added to the factory, which doubled capacity.[27] By 1815 the company employed 30 men and 30 boys.[41]

Difficult post–war period[edit]

"It is about ten years since the commencement of our establishment, and before our business was oppressed by the excessive importation of foreign glass, we gave employment to nearly a hundred hands, and maintained about four hundred persons; at present we find it difficult to furnish work for ten."

Bakewell, Page & Bakewell in a letter dated August 20, 1819[42]

The War of 1812 ended in 1814 with the Treaty of Ghent, which took effect in 1815.[43] During that year, Thomas Bakewell visited England to recruit more skilled glassworkers and to acquire samples of English glassware. Since glassworkers were still not allowed to emigrate, a warrant was issued for Bakewell's arrest—but he escaped detention.[44][Note 7] President James Madison retained wartime duties on imports until 1816.[46] At that time, England began dumping low–priced glass products in the United States while keeping its price for red lead high.[14]

The introduction of the steamboat in the United States enabled imports to move from the port of New Orleans up the Mississippi River to the western markets of the United States—which affected Pittsburgh glassmakers.[46] Another glass manufacturer in Pittsburgh, Bolton and Encell, failed in the summer of 1818 because of the foreign competition.[47] Page wrote that "from the beginning of 1817 till about the middle of 1822 we were literally gasping for breath".[48] The British/English competition caused other American glass factories to shut down, and by 1820 there were only 33 glassmaking facilities in the United States.[14] Bakewell used 80 to 100 tons of raw materials in 1815, but only used 20 tons in 1820. Its workforce changed from 30 men and 30 boys to 10 men and 12 boys.[44]

Bottle works[edit]

The first attempt at a black bottle side project by the Bakewell partners had a short life.[Note 8] A partnership called Page, Bakewell & Bostwick existed in 1814 and 1815.[50] Page eventually believed that newcomer Henry Bostwick, who represented himself to be a glassblower, was instead a very intelligent fraud. He also believed that Bostwick planned to convince Bakewell to replace Page with Bostwick in all connections. Bostwick, who was married to Page's wife's sister, left town a few months after his wife died suddenly in September 1815.[51]

Thomas Pears, a former employee of Bakewell in New York who had most recently been involved with a sawmill project in Kentucky, was hired by Bakewell, Page & Bakewell in 1816 to lead in another try at a bottle works startup.[52] Pears went to England and France in 1816 and 1818 to recruit workers, and family members believe he used a disguise to evade authorities.[53] Pears' new bottle works, called the Pittsburgh Porter Bottle Manufactory, was located adjacent to the Pittsburgh Glass Manufactory. While the older works made high quality flint glass, the bottle works used lower quality glass known as "black glass".[54] The company associated with the bottle works was called Thomas Pears and Company. Its partners were Pears, Page, and the two Bakewells. Production began in March 1819, but the company failed in less than one year.[55] The partners then turned their focus on saving their flint glass business.[56]

Publicity and sales[edit]

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The associate curator of decorative arts at the Yale University Art Gallery has commented that "Benjamin Bakewell understood showmanship".[57] In 1816, Bakewell presented two decanters to President Madison that generated publicity for his company.[58] When President James Monroe visited in September 1817, Bakewell also presented him with a pair of elegant cut glass decanters. Monroe ordered glassware, which helped to deflect criticism about imported furnishings at the White House. The total bill for the White House glassware was $1,032 (nearly equal to the company's total cash assets and equivalent to $19,685 in 2023).[59] The presentation objects and order for the White House enhanced the Bakewell reputation. The "diamond cut glass Monroe pattern" became a stock item for Bakewell.[60]

Sales downriver[edit]

After the failure of the bottle works, Thomas Pears began selling Bakewell glass and collecting debt for the company. This lasted from 1820 to 1822.[61] Much of this work was done downriver from the Pittsburgh Glass Manufactory, at places such as Cincinnati and Nashville.[62] Letters written by Pears to his wife discuss additional locations, such as Wheeling, Louisville, and St. Louis.[63] Selling any products was difficult because the people in the American west had very little money. In some cases, barter goods were accepted in lieu of money.[64][Note 9] Although Bakewell products were difficult to sell, the Bakewell glassware compared favorably with glassware from England and France. Cut and engraved glassware at times featured greyhounds, which were a symbol of friendship. The greyhound motif was a favorite in French–made glassware.[66]

Benjamin Bakewell also got involved in sales downriver.[62] In addition to the western states, Bakewell worked to strengthen market share in eastern markets such as New York and Philadelphia.[67] While Benjamin Bakewell traveled often from 1820 through 1823, Thomas Bakewell and Benjamin Page remained in Pittsburgh for most of that time and ran the glass works.[68] In March 1823 the company added a new furnace as part of a plan to sell more lower cost tableware.[69] Page moved to Cincinnati in early 1823 to sell glassware and other items, but returned by September. During that month he renewed his partnership with Benjamin Bakewell, and Thomas Bakewell joined the partnership.[70] By 1824, the company was advertising "moulded glass".[71]

Prosperity returns[edit]

Senator Henry Clay and Pittsburgh Congressman Henry Baldwin were supporters of the American System, which was an economic plan to nurture domestic industry by protective tariffs and improvements to the nation's infrastructure.[72] Bakewell promoted the American System with flasks and decanters that had American System inscribed on the glassware.[73] The flask was made of pressed glass decorated with a sheaf of rye on one side and a steamboat encircled with "The American System" on the other.[74]The American glass industry finally got relief from English imports with a protective tariff known as the Tariff of 1824.[75]

In 1824, Bakewell entered a set of decanters in the first Franklin Institute fair, and the decanters received honorable mention.[76] A year later, the Franklin Institute awarded Bakewell a medal for the best cut glass.[77] American Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette began touring the United States in 1824, and he arrived in Pittsburgh in 1825. Lafayette was presented two cut glass vases on May 31 after a tour of Bakewell's glass factory.[78] Bakewell produced commemorative tumblers to capitalize on Lafayette's popularity. A limited number of these tumblers were sulphide portrait versions, which had a portrait of Lafayette in its base. [79]

During 1825 Bakewell employed 61 glassworkers plus 12 engravers and ornamenters. About $45,000 (equivalent to $1,211,824 in 2023) worth of glass products were produced, and the plant's furnace consumed 30,000 bushels of coal.[80] During that year Bakewell sent a pair of cut and engraved celery glasses to Rachel Jackson, wife of Senator (and Battle of New Orleans hero) Andrew Jackson.[81][Note 10] This led to Jackson's purchase of Bakewell glassware for the White House after Jackson became President of the United States, and another purchase in 1832 for use at Jackson's home (The Hermitage) in Tennessee.[83] The Tariff of 1824 proved successful, as nearly 70 glass factories were started in the United States between 1820 and 1840.[75]

Mechanical pressing[edit]

John Palmer Bakewell, son of Benjamin, applied for a patent on September 9, 1825, for an "improvement in making glass furniture knobs".[84] For many years, this was assumed to be the first mechanical pressing patent. Patent records between 1790 and 1836 were destroyed in a fire, so some uncertainty exists concerning who had the first mechanical pressing–related patent.[84][Note 11] At least nine patents related to pressing glass were filed by companies across the United States by the end of 1830.[86]

Although pressing glass by hand had long existed, mechanical pressing of glass did not exist until the 1820s.[84] The use of a machine to press glass enabled two workers to produce four times as much glassware as a group of three or four glassblowers.[87] Mechanical pressing reduced the time and labor necessary to make glass products, which resulted in lowered costs that made glass products available to more of the public.[88] One author called mechanical pressing "the greatest contribution of America to glassmaking, and the most important development since the Romans discovered glassblowing...."[87]

Middle years[edit]

John Palmer Pears, son of Thomas Pears and grandson of John Palmer, was hired in 1826 at the age of seventeen. He would become plant manager in 1835.[89] Another namesake of John Palmer and son of Benjamin Bakewell, John Palmer Bakewell, became a partner of the company in September 1827, which caused the company to be renamed Bakewell, Page & Bakewells. During the year Benjamin Bakewell Atterbury, a nephew of Benjamin Bakewell, was hired to work as a clerk at the company.[90][Note 12] Although the company still emphasized its luxury glassware, its ordinary goods carried the company financially.[92] The Bakewell, Page & Bakewells partnership expired during September 1832. At that time Benjamin Page left the partnership and retired to Cincinnati. The company renamed itself Bakewells and Anderson. This partnership consisted of Benjamin Bakewell and his two sons, and Alexander M. Anderson—who was married to Benjamin's niece Sarah. This partnership lasted only until 1835, but the name was not changed until 1836. At that time the company name was changed to Bakewells and Company, and the partnership consisted of the three Bakewells.[93][Note 13]

The United States economy was not good during the late 1830s, and this caused Bakewells and Company to shut down its furnaces for four months during 1838. Although they shut their furnaces for only one week 1839, they asked some employees to work half time during 1840.[89] The health of some members of the Bakewell was deteriorating at this time. John Palmer Bakewell retired July 31, 1842, and he died less than four months later. Benjamin Bakewell, who had been active in the company despite being over 75 years old, died in February 1844 after a lingering illness.[94] Between the deaths of the two Bakewells, the company was reorganized effective August 1, 1842, as Bakewells and Pears. The partners were Benjamin Bakewell, Thomas Bakewell, and John Palmer Pears.[50] After the death of Benjamin Bakewell, the company was reorganized effective August 1, 1844, as Bakewell, Pears and Company.[94] Partners were Thomas Bakewell, John Palmer Pears, and Benjamin Page Bakewell.[50][Note 14] Thomas Bakewell led the new company.[34]

Big changes[edit]

In 1845 a massive fire in Pittsburgh destroyed over 1,000 buildings, including the Bakewell glass works and its warehouse.[96] The factory was rebuilt in 1846, and products consisting of green glass and flint glass were produced.[97] Thomas Bakewell continued his role as senior partner. While the old version of the company was a leader in cut and engraved crystal glassware, luxury goods were now only a small niche of the portfolio of glass products. Instead, the company relied upon mass-produced pressed glass.[98]

In 1854 the glass works was moved south across the Monongahela River to Bingham Street, between Eighth and Ninth Streets.[25] The new facility occupied the entire block with two ten-pot furnaces, cutting and engraving shops, offices and a showroom. The warehouse on the north side of the river (31 and 33 Wood Street) remained in use for another two decades.[99]

During the same year in August, Benjamin Bakewell Campbell joined the partnership. Campbell, who left his law practice, was a grandson of Benjamin Bakewell.[99] Unlike past changes in partners, the firm kept the same name. One can speculate that the name was kept the same to preserve brand identity, but the true reason is unknown.[100] In August 1859 Benjamin Bakewell Jr., son of John Palmer Bakewell, joined the partnership. Jacob W. Paul, brother-in-law of John Palmer Pears, became a partner in 1864—while Benjamin Page Bakewell retired in August. By 1865, the company was worth $500,000 (equivalent to $9,952,174 in 2023).[101]

Thomas Bakewell, senior partner of the company, died suddenly on May 30, 1866.[102] He had devoted 57 years to the glass business, and led the company since 1844.[99] John Palmer Pears, who joined the firm in 1842, became the senior partner.[65]

Decline[edit]

The United States economy went into a 32–month recession beginning April 1865. Another recession started June 1869 and lasted 18 months.[103] An economic depression, which became known as the Long Depression and featured the Panic of 1873, started October 1873 and continued through March 1879.[104] For the period of 1870 through 1879, three years had no changes in consumer prices while the other years all had decreases (deflation) ranging from 2.9 to 9.4 percent.[105] It was difficult to sell glassware. In Pittsburgh alone, there were 41 flint glass works in 1876—but only 30 by 1880.[106] Bakewell, Pears and Company is known to have shut its furnaces down for at least some time in 1873.[107]

Earlier, in 1864, William Leighton of the J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company had discovered a new formula for glass. This new type of glass was called soda–lime or lime glass, and the glass produced was very close in quality to crystal—but without the costly lead additive. This type of glass gradually replaced lead crystal for high quality glassware.[108] Bakewell, Pears and Company adopted this new formula for glass, and they used improved soda that made better quality glass. They also continued to make lead-formula glass. Between 1868 and 1874, partners in the company also received patent related to pressing, molds, and encased glass.[109]

John P. Pears died in 1874

Three men have been deemed responsible for the success of the company: founder Benjamin Bakewell, his son Thomas Bakewell who was senior partner from 1844 until 1866, and John Palmer Pears who led the company from 1866 until 1874.[65]

Talent provider[edit]

Notes[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Benjamin Bakewell's wife's sister married John Palmer. Their daughter married Thomas Pears who became a partner in a bottle project for Bakewell's glass company. Other family members who became partners in Bakewell's glass company include John Palmer Pears, Jacob W. Paul, Thomas Clinton Pears, Harry Palmer Pears, and Benjamin Bakewell Pears.[3]

- ^ Direct descendants of Benjamin Bakewell that became partners in his glass company include his sons Thomas Bakewell and John Palmer Bakewell, and Benjamin Bakewell Jr. (son of J.P. Bakewell). Benjamin Bakewell Campbell also became a partner, and he was Benjamin Bakewell's grandson through his daughter Nancy.[3]

- ^ An insurance description dated August 19, 1808, indicates the Bakewell (Bakewell and Ensell) glass factory was completed and operating.[17] The company was selling its glass by November 9, 1808, because it ran an advertisement in the local newspaper–and the works may have been in operation as early as February 1808 based on a newspaper notice concerning a glassmaking raw material.[20]

- ^ Pittsburgh's Bakewell glass company had nine different names. Bakewell, Pears & Company was the name used for the longest time. The names are:

Bakewell & Ensell (1808–1809);

Benjamin Bakewell & Company (1809–1813);

Bakewell, Page & Bakewell (1813–1827);

Bakewell, Page & Bakewells (1827–1832);

Bakewells & Anderson (1832–1836);

Bakewells & Company (1836–1842);

Bakewell & Pears (1842–1844);

Bakewell, Pears & Company (1844–1880); and

Bakewell, Pears Company, Ltd. (1880–1882).[25] - ^ Because glass plants at that time melted their ingredients in a pot, a plant's number of pots was often used to describe a plant's capacity. The ceramic pots were located inside the furnace. The pot contained molten glass created by melting a batch of ingredients that typically included sand, soda, lime, and other ingredients.[28] For comparison purposes, Wheeling's Barnes, Hobbs, and Company had ten-pot, nine-pot, and five-pot furnaces in 1857.[29]

- ^ On the American east coast, Deming Jarves' New England Glass Company was not producing red lead using domestic sources until 1819.[40]

- ^ A member of the Pears family wrote that Benjamin Bakewell "had a very narrow escape from the English authorities", but only mentions Thomas Bakewell as having "succeeded in bringing back a number of workers."[45]

- ^ Black glass is black in color because manganese oxide mixed with iron oxide has been added to the glass ingredients. In some cases, black glass appears black in normal lighting, but is actually a very dark brown, green, blue, or purple.[49]

- ^ Thomas Pears worked as a bookkeeper for Bakewell in 1823 and 1824. In 1825, he moved with his family to an experimental community based on communism located in New Harmony, Indiana. He returned to Pittsburgh with his family in 1826, and is thought to have worked again at Bakewell. He died from pneumonia in 1832 after moving back into his house too soon after a flood. He was only 46 years old at the time of his death, and his wife died a few days later. Neither lived long enough to see their son, John Palmer Pears, become manager of the Bakewell glass factory.[65]

- ^ Celery was a luxury food during the early 19th century. It was usually brought to the dinner table in elegant ware.[82]

- ^ Henry Whitney and Enoch Robinson of New England Glass Company received a pressing–related patent in 1826; and Phineas C. Dummer, George Dummer, and James Maxwell of the Jersey City Glass Works received pressing and mold–related patents in 1828.[85]

- ^ At least two members of the Atterbury family, Benjamin Bakewell Atterbury and James Seaman Atterbury, worked for the Bakewells—and they were descendants of Benjamin Bakewell's sister Sarah.[91]

- ^ Alexander M. Anderson married Sarah Bakewell, daughter of Benjamin Bakewell's brother William.[91] Anderson was a partner in the Bakewell company during the early 1830s.[50]

- ^ Benjamin Page Bakewell was grandson of both William Bakewell (Benjamin's brother) and Benjamin Page, who was one of the company's founders.[95]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 15–16

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 18; Pears, III 1948, p. 62

- ^ a b Palmer 2004, p. 195

- ^ a b c d Palmer 1979, p. 5

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 16

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 17

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 19

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 18

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 19; Pears, III 1948, p. 62

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 19–20

- ^ a b Palmer 2004, p. 24

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 23

- ^ "Confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, Pittsburgh, P.A." McConnell Library, Radford University. Archived from the original on February 21, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Skrabec 2011, p. 19

- ^ Killikelly 1906, p. 133; Palmer 2004, p. 24

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 23–24

- ^ a b c d Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 30

- ^ Bakewell 1896, p. 90

- ^ Killikelly 1906, p. 133; Jarves 1854, p. 43; Palmer 2004, p. 22

- ^ McKearin & McKearin 1966, p. 138

- ^ Skrabec 2011, p. 18

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 25; Killikelly 1906, p. 133; Jarves 1854, p. 43

- ^ a b c Killikelly 1906, p. 134

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 25

- ^ a b Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 144

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 24; "Pittsburgh Flint Glass Manufactory - Benjamin Bakewell & Co. (advertisement)". Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette. June 29, 1810. p. 4.

...have recently enlarged their assortment of glassware...

- ^ a b c Jarves 1854, p. 45

- ^ Skrabec 2007, pp. 25–26

- ^ "Manufacture of Glassware in Wheeling (page 2 second column from left)". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). August 29, 1857. Archived from the original on July 20, 2023. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 86

- ^ Jarves 1854, p. 44

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 26; "Pittsburgh Flint Glass Manufactory - Benjamin Bakewell & Co. (advertisement)". Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette (Ancestry). November 9, 1810. p. 4.

...have recently enlarged their assortment of glassware...

- ^ Knittle 1927, pp. 210, 307

- ^ a b Bakewell 1896, p. 50

- ^ Skrabec 2011, p. 20; Jarves 1854, p. 44

- ^ "Notice (column 3 near top)". Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette (Ancestry). May 31, 1811. p. 3.

The partnership heretofore existing...was dissolved....

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 28

- ^ a b c Palmer 2004, p. 29

- ^ Scoville 1944, p. 197

- ^ Skrabec 2011, p. 20

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 33

- ^ Bakewell, Page & Bakewell 1893, p. 28

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 33–34

- ^ a b Palmer 2004, p. 35

- ^ Pears, III 1948, p. 62

- ^ a b Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 34

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 38

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 36

- ^ Shotwell 2002, p. 41

- ^ a b c d Palmer 2004, p. 14

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 34

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 36

- ^ Pears, III 1948, p. 64

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 37

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 39; Pears, III 1948, p. 65

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 39

- ^ Gordon 2018, p. 47; "Gallery Talk with curator John Stuart Gordon: Material Culture of the Civil War and Reconstruction". Yale University Directed Studies. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ Gordon 2018, p. 47; Reif, Rita (March 17, 1985). "Antiques: Two Decanters Create a Stir". New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 42

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 42–43

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 73

- ^ a b Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 74

- ^ Pears, III 1948, p. 67

- ^ Pears, III 1948, p. 68

- ^ a b c Pears, III 1948, p. 70

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 46–47

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 48

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 45

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 48–49

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 45–46

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 50

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 50–51

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 51–52

- ^ Shotwell 2002, p. 15

- ^ a b Dyer & Gross 2001, p. 23

- ^ Gordon 2018, p. 47

- ^ Pears, Jr. 1925, p. 200

- ^ Gordon 2018, p. 47; "Marquis de Lafayette". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ Palmer 1979, pp. 9–10

- ^ Knittle 1927a, p. 206

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 52–53

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 53

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 71–72

- ^ a b c Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 42

- ^ Shotwell 2002, p. 44

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 43

- ^ a b Zerwick 1990, p. 79

- ^ "Pressed Glass: 1825–1925". Corning Museum of Glass. Archived from the original on March 23, 2024. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ a b Palmer 2004, p. 75

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 63

- ^ a b Palmer 2004, p. 194

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 64

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 14, 73

- ^ a b Palmer 2004, pp. 14, 75

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 14, 194

- ^ "Awful Calamity! City of Pittsburgh in Ruins". American Republican and Baltimore Daily Clipper. April 14, 1845. p. 1.

...from 1,000 to 1,200 buildings, of all descriptions...were reduced to ashes.

; Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 144 - ^ Palmer 2004, p. 76

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 76–77

- ^ a b c Palmer 2004, p. 79

- ^ "Branding". American Marketing Association. Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ Palmer 2004, pp. 14, 79

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 79; Bakewell 1896, p. 50

- ^ "US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions". National Bureau of Economic Research. Archived from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved 2023-03-31.

- ^ "US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions". National Bureau of Economic Research. Archived from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved 2023-03-31.; "Crisis Chronicles: the Long Depression and the Panic of 1873". Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ "Consumer Price Index, 1800-". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 88

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 80

- ^ Zembala & Clement 1973, p. 6

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 81

References[edit]

- Bakewell, Benjamin Gifford (1896). The Family Book of Bakewell, Page, Campbell; Being Some Account of the Descendants of John Bakewell... Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: W.G. Johnston & Co. OCLC 475684153. Archived from the original on May 15, 2024. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- Bakewell, Page & Bakewell (July 1893). "Correspondence – Glass Making in 1819". American Economist. XII (3): 28. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- Dyer, Davis; Gross, Daniel (2001). The Generations of Corning: The Life and Times of a Global Corporation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19514-095-8. OCLC 45437326.

- Gordon, John Stuart (2018). American Glass: The Collections at Yale. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Art Gallery in association with Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30022-669-0. OCLC 1024165135.

- Jarves, Deming (1854). Reminiscences of Glass–making. Boston, Massachusetts: Eastburn's Press. OCLC 14284772. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- Killikelly, Sarah (1906). The History of Pittsburgh: Its Rise and Progress. Chirora, Pennsylvania: Mechling Bookbindery. OCLC 1017019033. Archived from the original on May 15, 2024. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- Knittle, Rhea Mansfield (1927). Early American Glass. New York, New York: The Century Co. OCLC 1811743. Archived from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- Knittle, Rhea Mansfield (March 1927a). "Concerning William Peter Eichbaum and Bakewell's". Antiques. 11 (3): 205–206. Archived from the original on May 14, 2024. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- Madarasz, Anne; Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania; Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center (1998). Glass: Shattering Notions. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-0-93634-001-2. OCLC 39921461.

- McKearin, George S.; McKearin, Helen (1966). American Glass. New York City: Crown Publishers. OCLC 1049801744.

- Moore, N. Hudson (1924). Old Glass, European and American. New York City: Frederick A. Stokes Co. OCLC 1738230. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- Palmer, Arlene (1979). "American Heroes in Glass: The Bakewell Sulphide Portraits". American Art Journal. 11 (1). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, Smithsonian American Art Museum: 4–26. doi:10.2307/1594129. JSTOR 1594129. Archived from the original on February 24, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- Palmer, Arlene (2004). Artistry and Innovation in Pittsburgh glass, 1808-1882: from Bakewell & Ensell to Bakewell, Pears & Co. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Frick Art & Historical Center. ISBN 978-0-82294-252-8. OCLC 494286738.

- Pears, Jr., Thomas Clinton (October 1925). "Visit of Lafayette to the Old Glass Works of Bakewell, Pears and Co". Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. 8 (4): 195–203. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- Pears, Jr., Thomas C. (March 1927). "The First Successful Flint Glass Factory in America - Bakewell, Pears & Co. (1808–1882)". Antiques. 11 (3): 201–205. Archived from the original on May 14, 2024. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- Pears, III, Thomas C. (September 1948). "Sidelights on the History of the Bakewell, Pears & Company from the Letters of Thomas and Sarah Pears". Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. 31 (3): 61–70. Archived from the original on August 25, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- Scoville, Warren C. (September 1944). "Growth of the American Glass Industry to 1880". Journal of Political Economy. 52 (3): 193–216. doi:10.1086/256182. JSTOR 1826160. S2CID 154003064. Archived from the original on November 13, 2023. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- Shotwell, David J. (2002). Glass A to Z. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. pp. 638. ISBN 978-0-87349-385-7. OCLC 440702171.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007). Michael Owens and the Glass Industry. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1-45560-883-6. OCLC 1356375205.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007a). Glass in Northwest Ohio. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-73855-111-1. OCLC 124093123.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2010). The World's Richest Neighborhood: How Pittsburgh's East Enders Forged American Industry. New York City: Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-795-3. OCLC 615339678.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2011). Edward Drummond Libbey, American Glassmaker. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-78648-548-2. OCLC 753968484.

- Weeks, Joseph D.; United States Census Office (1884). Report on the Manufacture of Glass. Washington, District of Columbia: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 2123984. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- Zembala, Dennis (historian); Clement, Daniel (transcriber) (1973). "Seneca Glass Company" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record (Library of Congress). HAER WV–6. Morgantown, West Virginia: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior: – Written Historical and Descriptive Data. OCLC 20229044. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 2, 2023. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- Zerwick, Chloe (1990). A Short History of Glass. New York: H.N. Abrams in association with the Corning Museum of Glass. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-81093-801-4. OCLC 20220721.

External links[edit]

- Beck, Phillips – the Bakewells – and the Brunswick Pharmacal Co. - Society for Historical Archaeology

- Champagne Glass Bakewell, Pears & Co. - The Met

- Guide to Papers of the Bakewell–McKnight Family – University of Pittsburgh Library System