Samiri

Samiri | |

|---|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Musa |

|---|

|

|

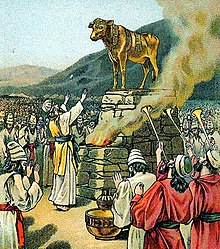

Samiri or the Samiri also known as Samaritan (Arabic: الْسَّامِريّ) is a phrase used by the Quran to refer to a rebellious follower of Moseswho created the golden calf and attempted to lead the Hebrews into idolatry. According to the twentieth chapter of the Quran, Samiri created the calf while Moses was away for 40 days on Mount Sinai, receiving the Ten Commandments.[1] In contrast to the account given in the Hebrew Bible, the Quran does not blame Aaron for the calf’s creation. Note: There are Muslim scholars who said he was not a follower of Moses, rather, someone who does not belong to the Israelites.

In the Quran[edit]

In Ta-Ha, the Quran’s twentieth surah, Moses is informed that Samiri has led his people astray in Moses’ absence. He returns to his people to berate them, and is informed of what Samiri has done.

- "They argued, “We did not break our promise to you of our own free will, but we were made to carry the burden of the people’s ˹golden˺ jewellery, then we threw it ˹into the fire˺, and so did the Sâmiri.” Then he moulded for them an idol of a calf that made a lowing sound. They said, “This is your god and the god of Moses, but Moses forgot ˹where it was˺!” Did they not see that it did not respond to them, nor could it protect or benefit them? Aaron had already warned them beforehand, “O my people! You are only being tested by this, for indeed your ˹one true˺ Lord is the Most Compassionate. So follow me and obey my orders.” They replied, “We will not cease to worship it until Moses returns to us.” Moses scolded ˹his brother˺, “O Aaron! What prevented you, when you saw them going astray, from following after me? How could you disobey my orders?” Aaron pleaded, “O son of my mother! Do not seize me by my beard or ˹the hair of˺ my head. I really feared that you would say, ‘You have caused division among the Children of Israel, and did not observe my word.’”

- Moses then asked, “What did you think you were doing, O Sâmiri?” He said, “I saw what they did not see, so I took a handful ˹of dust˺ from the hoof-prints of ˹the horse of˺ the messenger-angel ˹Gabriel˺ then cast it ˹on the moulded calf˺. This is what my lower-self tempted me into.” Moses said, “Go away then! And for ˹the rest of your˺ life you will surely be crying, ‘Do not touch ˹me˺!’ Then you will certainly have a fate that you cannot escape. Now look at your god to which you have been devoted: we will burn it up, then scatter it in the sea completely.”"Quran 20:87-95[2]

In surah Al-A'raf.

''When Moses returned to his people, ˹totally˺ furious and sorrowful, he said, “What an evil thing you committed in my absence! Did you want to hasten your Lord’s torment?” Then he threw down the Tablets and grabbed his brother by the hair, dragging him closer. Aaron pleaded, “O son of my mother! The people overpowered me and were about to kill me. So do not ˹humiliate me and˺ make my enemies rejoice, nor count me among the wrongdoing people.”[3] Al-A'raf:150

In Islamic tradition[edit]

The Quran’s statement that Samiri’s calf made a "lowing" sound has resulted in much speculation. A number of Islamic traditions say that the calf was made with dust trodden upon by the horse of the angel Gabriel, which had mystical properties. Some traditions say that the calf could also move, a property granted to it by the dust of the “horse of life”.[4] Stories indicate that he was a magician[5] Other traditions suggest that Samiri made the sound himself, or that it was only the wind.[6]

Later traditions expand upon the fate of those who worshiped the calf. Works by al-Tabari include a story in which Moses orders his people to drink from the water into which the calf had been flung; those guilty of worshiping it were revealed when they turned a golden hue.[7]

Samiri's punishment has been interpreted as total social isolation by most scholars.[8]

Possibilities suggested by Muslim scholars about his identity[edit]

A person from the children of Israel[edit]

Samiri has been linked to the rebel Hebrew leader Zimri on the basis of their similar names and a shared theme of rebellion against Moses’ authority.[9]

The second possibility is that this is his nickname because`In Arabic the names that contain (Sha) in Hebrew are often made into (Sa) and ghalban at the same time, changing the position of the letters of the name or deleting one of them and replacing it with another, and sometimes both occur.[10] Some have suggested that his name in Hebrew be (Shamari) In Arabic (شامري) because he is from the descendants of Shimron, son of Issachar, but when his name when was transferred to Arabic became known as Samari instead[11]

A person from Erev Rav[edit]

As from Egypt[edit]

It was said that he was a resident of Egypt who worships cows.

Evidence of this possibility is Hesat is an ancient Egyptian goddess in the form of a cow. She was said to provide humanity with milk (called "the beer of Hesat") and in particular to suckle the pharaoh and several ancient Egyptian bull gods. In the Pyramid Texts she is said to be the mother of Anubis and of the deceased king. She was especially connected with Mnevis, the living bull god worshipped at Heliopolis, and the mothers of Mnevis bulls were buried in a cemetery dedicated to Hesat. In Ptolemaic times (304–30 BC) she was closely linked with the goddess Isis.[12]

The evidence that supports the possibility that he is Egyptian is the large number of names in Egypt from which the name Samiri could be derived or be the reason for his nickname Samiri like some priests in ancient Egypt were called "Samart" and the priest Samart[13]

As from India[edit]

It was said that he was one of a people who worshiped cows in India, so his family settled in the land of Egypt, and he entered the religion of the Children of Israel outwardly, and in his heart was the worship of cows.[14]

Evidence of this possibility is the trade between ancient Egypt and ancient India, India artifacts like pots or cosmetic cases were discovered in ancient Alexandria. Painted on these pots were pictures of Ancient Egyptian gods like Anobees. Another surprising discovery in India was a collection of small bronze statues of Ancient Egyptian god Horus in the ancient Indian city of Gandahar..[15]

The other clue is the name Zamorin, which is used in India, and it is possible that it was translated into Samiri name or that is his nickname beacuse he came out there[16]

In Jewish tradition[edit]

There are three opinions about who actually formed the calf,

- Aaron formed it by molding the form of a calf from the molten gold.6

- Sorcerers from the erev rav formed it using magic.7

- Micah, a member of the erev rav whose life had been saved by Moses, created the calf. When the Jewish people were leaving Egypt, Moses went to collect Joseph’s coffin to fulfill his request that his remains be redeemed together with the Jews. However, in an attempt to stop the Jews from leaving, the Egyptians had sunk Joseph’s coffin in the Nile. Moses took a plaque, wrote on it the words “alei shor” (“rise ox”), and threw it in the river, causing the coffin of Joseph (who is compared to an ox) to rise to the surface. Micah had stolen this plaque and now used it to create the calf by throwing it into the blaze.8[17]

Ibn Ezra says about Erev Rav that they were mostly Egyptians, and Shadal (Rabbi Shmuel David Luzzatto, 1800-1865) says they were Egyptians that had intermarried with Jews. [18]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ The Qur'an, Surah Ta Ha, Ayah 85

- ^ quran.com https://quran.com/20?startingVerse=87. Retrieved 2024-05-05.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ quran.com https://quran.com/al-araf/150-160. Retrieved 2024-05-05.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ al-Tabari, Abu Jafar (1991). The History of al-Tabari, Volume III: The Children of Israel. Translated by Brinner, William M. p. 72.

- ^ "ص223 - كتاب صفوة التفاسير - - المكتبة الشاملة". shamela.ws. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ Rubin, Uri. "Tradition in Transformation: the Ark of the Covenant and the Golden Calf in Biblical and Islamic Historiography," Oriens (Volume 36, 2001): 202.

- ^ al-Tabari, Abu Jafar (1991). The History of al-Tabari, Volume III: The Children of Israel. Translated by Brinner, William M. p. 74.

- ^ Albayrak, I. (2002). Isra’iliyyat and Classical Exegetes’ Comments on the Calf with a Hollow Sound Q.20: 83-98/ 7: 147-155 with Special Reference to Ibn ’Atiyya. Journal of Semitic Studies, 47(1), 39–65. doi:10.1093/jss/47.1.39

- ^ Rubin, Uri. "Tradition in Transformation: the Ark of the Covenant and the Golden Calf in Biblical and Islamic Historiography," Oriens (Volume 36, 2001): 202-203.

- ^ "اسم عيسى عليه السلام في لغة بني إسرائيل . - الإسلام سؤال وجواب". islamqa.info (in Arabic). Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ "ص139 - كتاب عصمة القرآن الكريم وجهالات المبشرين - ومما له صلة بموضوعنا واعترض به الطائش على الوحي الإلهي قوله إن القرآن قد ذكر أن الذي صنع العجل لبني إسرائيل في التيه هو السامري - المكتبة الشاملة". shamela.ws. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 173–174

- ^ "الآثار التي خلفها لنا ملوك الفرس | موسوعة مصر القديمة".

- ^ "من هو السامري الذي أضل قوم موسى؟". بوابة الوفد الإلكترونية (in Arabic). 2020-05-09. Retrieved 2024-05-05.

- ^ "Egypt, India: An age-old relationship". 23 August 2007.

- ^ "Zamorin | Indian ruler | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ^ "What Was the Golden Calf?".

- ^ Palvanov, Efraim (2022-01-06). "Israel's Greatest Enemy: The Erev Rav | Mayim Achronim". Retrieved 2024-05-06.