Naringenin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(2S)-4′,5,7-Trihydroxyflavan-4-one

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2S)-5,7-Dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one | |

| Other names

Naringetol; Salipurol; Salipurpol

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.865 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H12O5 | |

| Molar mass | 272.256 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 251 °C (484 °F; 524 K)[1] |

| 475 mg/L[citation needed] | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Naringenin is a flavanone from the flavonoid group of polyphenols.[2] It is commonly found in citrus fruits, especially as the predominant flavonone in grapefruit.[2]

The fate and biological functions of naringenin in vivo are unknown, remaining under preliminary research, as of 2024.[2] High consumption of dietary naringenin is generally regarded as safe, mainly due to its low bioavailability.[2] Taking dietary supplements or consuming grapefruit excessively may impair the action of anticoagulants and increase the toxicity of various prescription drugs.[2]

Similar to furanocoumarins present in citrus fruits, naringenin may evoke CYP3A4 suppression in the liver and intestines, possibly resulting in adverse interactions with common medications.[2][3][4][5]

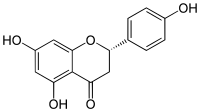

Structure[edit]

Naringenin has the skeleton structure of a flavanone with three hydroxy groups at the 4′, 5, and 7 carbons.[2] It may be found both in the aglycol form, naringenin, or in its glycosidic form, naringin, which has the addition of the disaccharide neohesperidose attached via a glycosidic linkage at carbon 7.

Like the majority of flavanones, naringenin has a single chiral center at carbon 2, although the optical purity is variable.[6][7] Racemization of (S)-(−)-naringenin has been shown to occur fairly quickly.[8]

Sources and bioavailability[edit]

Naringenin and its glycoside has been found in a variety of herbs and fruits, including grapefruit, oranges, and lemons,[2] sour orange,[9] sour cherries,[10] tomatoes,[11] cocoa,[12] Greek oregano,[13] water mint,[14] as well as in beans.[15] Ratios of naringenin to naringin vary among sources,[2] as do enantiomeric ratios.[7]

The naringenin-7-glucoside form seems less bioavailable than the aglycol form.[16]

Grapefruit juice can provide much higher plasma concentrations of naringenin than orange juice.[17]

Naringenin can be absorbed from cooked tomato paste. There are 3.8 mg of naringenin in 150 grams of tomato paste.[18]

Biosynthesis and metabolism[edit]

Naringenin can be produced from naringin by the hydrolytic action of the liver enzyme naringinase.[2] Naringenin is derived from malonyl-CoA and 4-coumaroyl-CoA.[2] The latter is derived from phenylalanine. The resulting tetraketide is acted on by chalcone synthase to give the chalcone that then undergoes ring-closure to naringenin.[19]

The enzyme naringenin 8-dimethylallyltransferase uses dimethylallyl diphosphate and (−)-(2S)-naringenin to produce diphosphate and 8-prenylnaringenin. Cunninghamella elegans, a fungal model organism of the mammalian metabolism, can be used to study the naringenin sulfation.[20]

Metabolic fate and research[edit]

The fate and biological roles of naringenin are difficult to study because naringenin is rapidly metabolized in the intestine and liver, and its metabolites are destined for excretion.[2][21] The biological activities of naringenin metabolites are unknown, and likely to be different in structure and function from those of the parent compound.[2][21]

References[edit]

- ^ Naringenin at the Human Metabolome Database

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Flavonoids". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University. 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ Lohezic-Le Devehat, F.; Marigny, K.; Doucet, M.; Javaudin, L. (2002). "[Grapefruit juice and drugs: a hazardous combination?]". Therapie. 57 (5): 432–445. ISSN 0040-5957. PMID 12611197.

- ^ Singh, B. N. (September 1999). "Effects of food on clinical pharmacokinetics". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 37 (3): 213–255. doi:10.2165/00003088-199937030-00003. ISSN 0312-5963. PMID 10511919.

- ^ Fuhr, U. (April 1998). "Drug interactions with grapefruit juice. Extent, probable mechanism and clinical relevance". Drug Safety. 18 (4): 251–272. doi:10.2165/00002018-199818040-00002. ISSN 0114-5916. PMID 9565737.

- ^ Yáñez JA, Andrews PK, Davies NM (April 2007). "Methods of analysis and separation of chiral flavonoids". Journal of Chromatography. B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences. 848 (2): 159–181. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.052. PMID 17113835.

- ^ a b Yáñez JA, Remsberg CM, Miranda ND, Vega-Villa KR, Andrews PK, Davies NM (March 2008). "Pharmacokinetics of selected chiral flavonoids: hesperetin, naringenin and eriodictyol in rats and their content in fruit juices". Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition. 29 (2): 63–82. doi:10.1002/bdd.588. PMID 18058792. S2CID 24051610.

- ^ Krause M, Galensa R (July 1991). "Analysis of enantiomeric flavanones in plant extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography on a cellulose triacetate based chiral stationary phase". Chromatographia. 32 (1–2): 69–72. doi:10.1007/BF02262470. ISSN 0009-5893. S2CID 95215634.

- ^ Gel-Moreto N, Streich R, Galensa R (August 2003). "Chiral separation of diastereomeric flavanone-7-O-glycosides in citrus by capillary electrophoresis". Electrophoresis. 24 (15): 2716–2722. doi:10.1002/elps.200305486. PMID 12900888. S2CID 40261445.

- ^ Wang H, Nair MG, Strasburg GM, Booren AM, Gray JI (March 1999). "Antioxidant polyphenols from tart cherries (Prunus cerasus)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 47 (3): 840–844. doi:10.1021/jf980936f. PMID 10552377.

- ^ Vallverdú Queralt A, Odriozola Serrano I, Oms Oliu G, Lamuela Raventós RM, Elez Martínez P, Martín Belloso O (September 2012). "Changes in the polyphenol profile of tomato juices processed by pulsed electric fields". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 60 (38): 9667–9672. doi:10.1021/jf302791k. PMID 22957841.

- ^ Sánchez Rabaneda F, Jáuregui O, Casals I, Andrés Lacueva C, Izquierdo Pulido M, Lamuela Raventós RM (January 2003). "Liquid chromatographic/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometric study of the phenolic composition of cocoa (Theobroma cacao)". Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 38 (1): 35–42. Bibcode:2003JMSp...38...35S. doi:10.1002/jms.395. PMID 12526004.

- ^ Exarchou V, Godejohann M, van Beek TA, Gerothanassis IP, Vervoort J (November 2003). "LC-UV-solid-phase extraction-NMR-MS combined with a cryogenic flow probe and its application to the identification of compounds present in Greek oregano". Analytical Chemistry. 75 (22): 6288–6294. doi:10.1021/ac0347819. PMID 14616013.

- ^ Olsen HT, Stafford GI, van Staden J, Christensen SB, Jäger AK (May 2008). "Isolation of the MAO-inhibitor naringenin from Mentha aquatica L". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 117 (3): 500–502. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2008.02.015. PMID 18372132.

- ^ Hungria M, Johnston AW, Phillips DA (1992-05-01). "Effects of flavonoids released naturally from bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) on nodD-regulated gene transcription in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. phaseoli". Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 5 (3): 199–203. doi:10.1094/mpmi-5-199. PMID 1421508.

- ^ Choudhury R, Chowrimootoo G, Srai K, Debnam E, Rice-Evans CA (November 1999). "Interactions of the flavonoid naringenin in the gastrointestinal tract and the influence of glycosylation". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 265 (2): 410–415. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.1695. PMID 10558881.

- ^ Erlund I, Meririnne E, Alfthan G, Aro A (February 2001). "Plasma kinetics and urinary excretion of the flavanones naringenin and hesperetin in humans after ingestion of orange juice and grapefruit juice". The Journal of Nutrition. 131 (2): 235–241. doi:10.1093/jn/131.2.235. PMID 11160539.

- ^ Bugianesi R, Catasta G, Spigno P, D'Uva A, Maiani G (November 2002). "Naringenin from cooked tomato paste is bioavailable in men". The Journal of Nutrition. 132 (11): 3349–3352. doi:10.1093/jn/132.11.3349. PMID 12421849.

- ^ Wang C, Zhi S, Liu C, Xu F, Zhao A, Wang X, et al. (March 2017). "Characterization of Stilbene Synthase Genes in Mulberry (Morus atropurpurea) and Metabolic Engineering for the Production of Resveratrol in Escherichia coli". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 65 (8): 1659–1668. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.6b05212. PMID 28168876.

- ^ Ibrahim AR (January 2000). "Sulfation of naringenin by Cunninghamella elegans". Phytochemistry. 53 (2): 209–212. Bibcode:2000PChem..53..209I. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00487-2. PMID 10680173.

- ^ a b Rothwell JA, Urpi-Sarda M, Boto-Ordoñez M, Llorach R, Farran-Codina A, Barupal DK, Neveu V, Manach C, Andres-Lacueva C, Scalbert A (January 2016). "Systematic analysis of the polyphenol metabolome using the Phenol-Explorer database". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 60 (1): 203–11. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201500435. PMC 5057353. PMID 26310602.