Draft:Burmese-Chinese cuisine

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take 3 months or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 2,714 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

| Submission declined on 9 May 2024 by TheTechie (talk). Failure of WP:NOTGUIDE.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

This draft has been resubmitted and is currently awaiting re-review. |  |

| Submission declined on 7 May 2024 by ToadetteEdit (talk). This submission is not adequately supported by reliable sources. Reliable sources are required so that information can be verified. If you need help with referencing, please see Referencing for beginners and Citing sources. |  |

Comment: (edit conflict) ToadetteEdit! 07:55, 7 May 2024 (UTC)

Comment: (edit conflict) ToadetteEdit! 07:55, 7 May 2024 (UTC)

Burmese-Chinese Cuisine[edit]

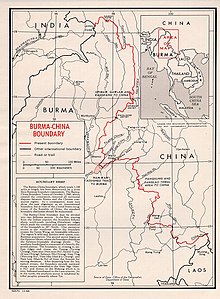

Burmese-Chinese cuisine is a fusion of culinary traditions and styles from Myanmar (also known as Burma) and China. It is derived from Chinese cuisine that was developed by Chinese Burmese, and the factor of influence is from the immigration of the Chinese people. Usually, the Burmese Chinese cuisine is prominently based on the southern part of China, which is rooted in Yunnanese, Fujian, and Guangdong since northern Myanmar is connected with the border of China[1]. Nonetheless, these dishes can be found from a dense community of Chinese people, such as Chinatown to the streetside food stands throughout the country.[2]

Chinese Influence on Burmese Cuisine[edit]

Chinese cuisine influence can be observed in several cities across Myanmar, notably in areas with significant Chinese populations or economic ties with China. Cities such as Mandalay, Yangon, Muse, Lashio, and Myitkyina exhibit strong Chinese culinary influences.[3] As regards ethnic Chinese-Myanmar relations, the historical and economic interactions between China and Myanmar have deep-seated origins, dating back to the early second millennium, notably marked by the Mongol Yuan dynasty's incursion in the thirteenth century, during their reign over China. [4]Following Myanmar's colonization in the 1850s, a considerable influx of Chinese merchants settled in Yangon, gradually establishing a prominent presence that evolved into a pivotal commercial center, recognized as Myanmar's Chinatown.[5]

In Myanmar, Chinatowns are primarily located in major urban centers with significant Chinese populations, particularly in cities like Yangon and Mandalay. It is characterized by bustling markets, traditional Chinese temples, and a plethora of Chinese-owned businesses and restaurants[6]. Mandalay also has its own Chinatown, albeit smaller in scale compared to Yangon Chinatown, featuring Chinese eateries, shops, and cultural landmarks. While these cities have the most prominent districts, other urban areas with sizable Chinese communities may also have smaller areas or clusters of Chinese-owned businesses.[7] The dishes that can be found along the streets of Chinatown serve as a distinct representation of Chinese identity within Myanmar's largest and most culturally diverse city.[8]

This cultural establishment has significantly contributed to the local economy, symbolizing the prosperity and expansion of Chinese enterprises within the region. China holds the position of Myanmar's largest trading partner, with agricultural goods constituting a significant portion of Myanmar's exports to China and serving as key contributors to the nation's foreign exchange reserves, while also being pivotal in efforts to alleviate the trade deficit.[9]

Owing to its proximity to mainland China and historical migration patterns, particularly evident in the northern regions, Myanmar has experienced the introduction of Chinese immigrants who have brought with them essential culinary ingredients and recipes from their homeland. These influences has an effect on Myanmar food such as Hokkien, Hakka, and Cantonese loanwords are used for various dishes such as Mala, Kung Bao Chicken, Ti Ke ( Chinese dessert), Pauk Si ( steamed buns) , Aw-Kae-Kyi ( steamed turnip cake). In terms of ingredients, it has now been thoroughly absorbed into the local cuisine. This includes items such as soy sauce, bean sprouts, bean curd, and noodles made from wheat, rice, and mung peas, which have become integral components of Chinese cuisine in Myanmar. In spicy dishes such as mala, Chinese spices like star anise, Sichuan pepper, and five-spice powder are often used. Chinese cooking techniques such as stir-frying and noodle dishes are also significant in Myanmar.

The soybean, a native of China, appears in many guises in Myanmar: soy sauce; fermented soybeans (sometimes pressed into a cake and dried); and beancurd. Taking their cue from the Chinese, the Shan people near the border create a unique beancurd using chickpeas. Beansprouts, a common vegetable in China, are made from several types of beans including soybeans and mung peas; They are eaten fresh or left to ferment and eaten as a salad or condiment. Sesame seeds and dried black mushrooms are other frequently used Chinese ingredients. Preserved sweet and sour fruits, such as tamarind, mango, Indian jujube, and plum, are common snacks and condiments for desserts in Myanmar, with a distinctively tangier flavor than those from China, often containing chili to suit local preferences.[10]

Chinese culture has a strong emphasis on food, and this is reflected in the vibrant culinary scenes in the cities. Burmese food became infused with Chinese culinary tradition and cultures. For instance, the Sino-Burmese community is associated with the cuisine that consists of many types of noodles. In Mandalay and other regions of northern Myanmar, Chinese Muslim or Hui people that live in that area created a dish that contains Chinese egg noodles fried together with tofu, spices, Chinese vegetables, such as Bok Choy, and chicken. In addition, Dining out is a habit that Chinese families frequently prioritize in order to spend quality time together. This tradition is similar to the banquet customs that are widely observed in Chinese communities worldwide. This can also demonstrate the representation of each heritage from their own original ancestry.[11]

Adaptation to Local Cuisine[edit]

There are different styles of Chinese food in Myanmar (Burma) depending on the location of Chinese immigrants.[12]

(1) Hakka Cuisine in Myanmar: Originating in the Chinese provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, and Yunnan, the Hakka people have introduced their culinary customs to Myanmar.[1]Hakka dishes are usually have a strong taste, salty are aromatic. Their soy-braised pork belly, which is similar to Hakka stews, is one of their signature dishes. They also utilize pickled radish tops and mustard greens, which are great in noodle soups. Other significant Hakka dishes are dried bamboo shoot stewed in broth, pork rib stew, stirred fried pork lungs with pineapple and wood-ear fungus, and stirred fried duck blood with garlic chives.[13][14]

(2) Kokang Cuisine in Myanmar: Kokang people from the northern part of Myanmar bring their food culture into the local food, mixed with Shan food such as Shan noodles and Meeshay.[15] Kokang dishes are mostly steamed with less oil and roasted. Some distinct Kokang cuisine in Myanmar includes meats and fish in combination with bamboo, pea shoots, tofu, lotus roots, quince and sour pickled vegetables, mala pork tongue salad, rice tofu salad, sour mustard soup, lettuce pork salad, and pork head salad.

(3) Yunnan Cuisine in Myanmar: Yunnan people are predominantly found in the northern and eastern parts of the country, near the border with China. The key flavours found in Yunnan cuisine include mint, lemongrass, lemon basil, lime, ginger, Qiubei chillies, coriander, spring onions, vinegar, and sweet soy sauce. Popular Yunnan dishes found in Myanmar are steamed pot chicken, Yunnan noodle, Yunnan hotpot, fried fish with chilli tomato paste, double-fried pork, and steamed egg with minced pork.[16][17][18]

(4) Cantonese Cuisine in Myanmar: Originating from Guangdong province in China, has made a significant impact on the culinary landscape of Myanmar.[19] Cantonese cuisine, such as stir-fried rice noodles with beef, shrimp dumplings, shaomai, and steamed stuffed buns called Baozi, Kung Pao chicken, Xiao Long Bao ( soup dumplings), and crispy roast duck are some popular Cantonese dishes to try in Myanmar.[11]

(5) Sichuan Cuisine in Myanmar - Significant tastes and smells of hot, mouth-numbing Mala dishes are blooming especially in the youth community. Mala Xiang Guo, Mala Mao Cai, and Mala grilled fish are some Sichuan dishes that are quite popular in Myanmar.[20]

(6) Hokkien/Fujian Cuisine in Myanmar - As the Fujian Chinese are the majority and significant group in Myanmar, Fujian cuisine has also influenced Burmese cuisine.[4]The main ingredients include soy sauce, ginger, bean sprouts, bean curd, dried mushrooms, etc giving earthy, light flavours. Some popular dishes are steamed buns, roasted duck, fried Chinese dough sticks, noodle dish, etc.

List of Burmese-Chinese Foods[edit]

Dishes[edit]

- Myu swun ( Burmese: မြူစွမ်; /mjùswàɴ/ , Chinese:线面; xiànmiàn ) - soft, thin wheat vermicelli, known as Misua in Singapore and Malaysia. It is usually served with chicken, pork, or beef broth or another way of serving is stir-fried with vegetables.

- Panthay khauk swè ( Burmese: ပန်းသေးခေါက်ဆွဲ; /páɴθékʰaʊʔsʰwɛ́/ , Chinese: 新疆维吾尔面; XīnjiāngWéiwúěrMiàn ) - Panthay means Chinese-Muslim and Khauk swe means noodle in Burmese language. It is a simple dish which includes chicken curry with noodles. It is usually made with fresh egg noodles, chicken, a variety of spices, and coconut milk. For the variations, different toppings are added to the dish, such as crushed peanuts, lime, cilantro, peppers, and crispy onions.[21][22]

- San byoke ( Burmese: ဆန်ပြုတ်; /sʰàɴbjoʊʔ/ , Chinese:油炸粿; yóuzháguǒ) - meaning boiled rice. It is a Burmese version of Chinese rice congee. It is made by cooking white short-grain rice until it has a soft and creamy porridge-like consistency. After that, adding onion oil or garlic oil brings a flavourful taste. The meat— fish, chicken, pork or duck can be added as a topping. Similar to other Southeast Asian countries, this is usually served as breakfast. Some people like to eat with fried dough sticks similar to the Chinese Youtiao.[23][24]

- Mala Dishes - The most recent popular Chinese culinary in Myanmar is spicy and numbing Chinese meals. According to Sean Yann, the manufacturer of the mala paste package, the spicy Chinese taste was introduced to Myanmar 10 years ago.[25]As it is common food among youths in 2021, the mala restaurants and street side stalls are always almost full of consumers, mostly non-Chinese people in Myanmar.[26]

- Mala Xiang Guo (Burmese:မာလာရှမ်းကော; /màlàʃáɴkɔ́/, Chinese:麻辣香锅; málàxiāngguō ) is usually cook in a large wok. It contained vegetables, meat, and meatballs along with its spicy, flavour-intense, tongue-numbing Chinese spices and pastes. The main ingredient that brings a tongue-tingling sensation is Sichuan peppercorn and the dry chilli pepper adds a smoky, spicy flavour and fragrance to this dish.[27][28]

- Mao Cai ( Burmese: မောက်ချိုက်; /maʊʔt͡ɕʰaɪʔ/, Chinese: 冒菜; màocài ) - one of the stew dishes which is originally from Sichuan. It is a bowl with various kinds of meats, meatballs and vegetables with mala paste. The preparation of this dish is that the ingredients contained need to be well-cooked in a soup and after that, put into the bowl with seasonings such as coriander or green onion, and sesame seeds. The taste is not as intense as Mala Xian Guo but it is spicy, hot and delicious. Usually, Mao Cai is a mini-hotpot for a single person or a group of people. It can be also served with hot rice along with the soup.[29][30][31]

- Mala Tang ( Burmese : မာလာထန် , Chinese : 麻辣烫; málàtàng) is served with bamboo skewers dipped into the boiling mala hot pot. Usually, the restaurants and stalls displayed a wide variety of skewer choices- meat, and vegetables. After the skewers are chosen, boil it into the mala stock pot. After it is cooked, take them out to eat. It is rarely served with rice and the soup is seldom drunk.[30]

- Mala Skewers ( Burmese: မာလာအကင်, Chinese: 麻辣烧烤; málàshākǎo ) Shaokao or Chinese barbeque can be seen at street food stalls or beer restaurants in Myanmar. The marinated pork, chicken, meatballs, tofu, seafood and vegetables-mushrooms, broccoli, carrots, asparagus and different varieties of skewers are displayed. After selecting the skewers on the tray, the waiter will grill them with some mala barbecue spices. Most of the Myanmar people serve them with Myanmar beer.[32]

- Mala Hotpot ( Burmese: မာလာဟော့ပေါ့, Chinese: 麻辣火锅; málàhuǒguō ) is one of the popular base soups to choose at hot pot restaurants. The raw ingredients chosen are boiled in the mala soup base. It is usually eaten with a customizable dipping sauce which contains peanut sauce, sesame oil, chilli sauce, garlic and other toppings depending on the individual’s preferences.[33]

- Kyay oh ( Burmese: ကြေးအိုး; /t͡ɕéʔó/) is a noodle soup with meat, meatballs, egg, tofu and pak choy. The taste is: The noodles can be chosen rice vermicelli or flat rice noodles or even mixed with these two noodles. The meat can be chosen as chicken, pork, fish and pork offal. It can be customized depending upon the individual’s preferences, such as served with or without broth ( dry version is called as Dry kyay oh salad; Burmese: Kyay-oh-sigyet; ကြေးအိုးဆီချက်; /t͡ɕéʔó sʰìd͡ʑɛʔ/ ). Moreover, we can choose from original taste or sour-spicy taste.[34] Although it did not appear in food history record until 1968, many people presume that Chinese ancestors might have invented the fusion with their recipe and available ingredients in Burma at that time.[35]

- Hpet Htoke - (Burmese: ဖက်ထုပ်; /pʰɛʔtʰoʊʔ/ , Chinese: 饺子; jiǎozi) . According to its etymology, ဖက် (hpak, “leaf”) + ထုပ် (htup, “parcel”). The Burmese version of wonton also consists of minced meat, garlic, pepper, salt and spring onions in a wonton wrapper. It can be served as steamed, soup, or dry with sesame oil/garlic oil/ spicy garlic oil). Moreover, it can be served the wonton separately or with the noodles.

- Meeshay - (Burmese: မြီးရှည်; [mjíʃè], Chinese: 米线; mǐxiàn ). This food is carried by the Yunnan-Chinese ethnic group brought to Myanmar. It can be commonly found in the middle and upper regions of Myanmar. The ingredients and serving differ depending on the region, but mainly, it can be divided into 3 types: Shan/Mogok Meeshay ( original meeshay) which is found in Shan State and Mogok, Mandalay Meeshay, a variation from the Mandalay region, and Myay-oh Meeshay ( Clay pot Meeshay). All the variations of Meeshay’s meat sauce is made with chicken or pork minced along with onions. The ingredients contain minced meat, soy sauce and chilli oil. The difference is that Mogok Meeshay contains brown tangy gel and Mandalay Meeshay includes cornstarch jelly-like gel.

- Htamin kyaw ( Burmese: ထမင်းကြော်; /tʰəmɪ́ɴd͡ʑɔ̀/, Chinese: 炒饭; chǎofàn) - According to its etymology, ထမင်း (hta.mang:, “rice”) + ကြော် (krau, “to fry”). This aromatic fried cuisine usually comprises cooked rice that has been stir-fried with a variety of ingredients, including eggs, vegetables, and with or without meat, peas, onions, garlic, and dark soy sauce. It is a versatile dish that can be served for breakfast, lunch, or dinner.[36]

- Khout Swal Kyaw ( Burmese: ခေါက်ဆွဲကြော်; /kʰaʊʔsʰwɛ́t͡ɕɔ̀/, Chinese: 炒面; chǎomiàn) is a typical Chinese stir-fried noodle with a variety of vegetables, meat such as chicken, pork, or shrimp, and seasoned with soy sauce, oyster sauce, garlic, and other spices. The dish is commonly found in Chinese restaurants, street food stalls, and local eateries across the country.

- Kyar San Kyaw ( Burmese: ကြာဆံကြော်; /t͡ɕàzàɴt͡ɕɔ̀/) is a stirred fried rice vermicelli. Like fried noodle, in this dish, instead of using noodles, it use rice vermicelli and the other ingredients are the same.[37]

- Kor Yay Khout Swal ( Burmese:ကော်ရည်ခေါက်ဆွဲ; /kɔ̀jìkʰaʊʔsʰwɛ́/ , Chinese: 卤面; lǔmiàn ) - known as a starchy gravy noodle. Because it originated from the Hokkien people of China, this cuisine is similar to Lor Mee. It is served with thick yellow rice noodles with gravy soup offering a comforting feeling. The gravy is typically produced with a combination of ingredients such as meat, vegetables, spices, and a starchy thickening such as corn starch or flour and beaten egg mixture to give it a rich and velvety smoothness.[38]

- Kung Pao chicken ( Burmese: ကြက်သားကုန်းဘောင်ကြီးကြော်; /t͡ɕɛʔθákóʊɴbàʊɴd͡ʑít͡ɕɔ̀/ , Chinese: 宫保鸡丁; gōng bǎo jī dīng) - the word is directly borrowed from the Chinese language. The chicken is usually marinated with corn starch, soy sauce, pepper and sugar before cooking. This stirred-fried dish consists of small cubes of chicken breast, vegetables, chilli peppers, peanuts, sesame oil, chives, salt and oyster sauce. This dish is usually served along with steamed white rice.[39][40]

- Cho Chin Kyaw ( Burmese: ချိုချဉ်ကြော်; /t͡ɕʰòt͡ɕʰɪ̀ɴd͡ʑɔ̀/ ) is a sweet and sour dish of meat such as chicken, pork or other meatballs mixed with vegetables. The main ingredients is sweet and sour sauce, which is made up of chilli sauce, soy sauce, vinegar, and cooking wine.

Appetizers[edit]

- Wat Thar Late Kyaw ( Burmese: ဝက်သားလိပ်, Chinese: 五香肉卷; wǔxiāngròujuǎn) - is a fried five-spice pork rolls similar to the Lor Bak/Ngoh Hiang. The ingredients consists of thinly sliced pork minced rolled with a mixture of aromatic spices such as five-spice powder, garlic, ginger, soy sauce, sugar, green onions, onions, sesame oil, dried soya bean skins and corn starch.[41]

- Aw-kae-kyi ( Burmese: အော်ကေ့ကြည်;/ʔɔ̀kḛt͡ɕì/, Chinese:芋头糕; yùtougāo) - this word was borrowed from Min Nan- Hokkien Chinese. The meaning of its is “turnip cake” similar to “Lo bak go”. It has 3 variations: turnip, carrot or radish. In some countries, this is known as "fried carrot cake" or "carrot cake." The ingredients include grated turnips, radish or carrot, rice flour, corn starch, mushrooms, garlic, sugar, salt and pepper. After mixing the prepared ingredients well, steam it. Another way of eating is frying this steamed dish.[42]

- Pauk Si ( Burmese: ပေါက်စီ; /paʊʔsì/, Chinese: 包子; baozi) - a steamed bun filled with meat: chicken, pork, egg or sweet bean paste. It is a common warm snack that is offered all over the nation and is served in traditional tea shops. Depending on the vendor, it can be filled with a variety of ingredients such as pork, onion, egg, red chilli sauce, and other choices.[43]

- Tea Egg (Burmese: လက်ဖက်ကြက်ဥ; /ləpʰɛʔt͡ɕɛʔʔṵ/ , Chinese: 茶叶蛋; cháyèdàn ) - is a common side dish found in Mee Shay restaurants. Soy sauce, several Chinese spices such as star anise, cinnamon sticks, Sichuan peppercorns ,and tea leaves ,are used to marinate the hard-boiled eggs.[44]

- Wat Thar Kout Nyin Htoke ( Burmese: ဝက်သားကောက်ညှင်းထုပ်; /wɛʔθákaʊʔɲ̊ɪ́ɴtʰup/; Chinese: 粽子; zòng zi) - is a popular Chinese appetizer in Myanmar. It can be described as sticky rice with fillings wrapped with a bamboo leaf as a simple term. The main ingredients contain glutinous rice, pork belly, pork sausages, shiitake mushrooms, salted egg, beans, garlic, pepper, cashew nuts and dried prawns. The taste is a balance between sweet, salty and chewy. For the alternative meat, it can also be used as chicken filling.[45]

- Spring Roll (Burmese: ကော်ပြန့်စိမ်း; /kɔ̀pja̰ɴzéɪɴ/, Chinese: 春卷; chūn juǎn ) - is a roll of cooked vegetable with optional meat wrapped in a flour wrapper. It is very similar to Popiah. The main ingredients consist of carrot, cabbage, bean sprouts, tofu, garlic, pepper, soy sauce and other assorted vegetables, depending on the seller. It also varies in size and shape; some are sold in bite-sized or medium-sized rolls. The alternative way of serving is that fried spring roll ( Burmese: ကော်ပြန့်ကြော်; /kɔ̀pja̰ɴd͡ʑɔ̀/ ). This type of dish is crispy and crunchy on the outside and tender and flavourful on the inside. Both versions of spring rolls can be served along with sauce made up of chilli sauce, green onions, lemon, and garlic.[45]

- Kaw Kyaw ( Burmese:ကော်ကြော်;/kɔ̀t͡ɕɔ̀) is a pan-fried tapioca starch or potato starch with egg. It is similar to the fried oyster omelette, but in the Burmese version, it usually adds crab meat or chicken as a filling. After that, green onions and pepper can be added as garnishes.

- E Kya Kway (Burmese: အီကြာကွေး; /ʔìt͡ɕàkwé/, Chinese: 油条; Yóutiáo) is a deep fried long golden-brown dough stick usually eaten at breakfast. As its accompaniment, people usually eat with steamed sprouted yellow beans ( ပဲပြုတ်; Pe Pyote) salad made of salt and oil, dipped into a cup of coffee or tea, or added to the porridge. Moreover, it can be cut into small rings into mohinga as an additional. This is a popular breakfast appetizer and a necessary food for every tea shop in Myanmar.[46][47]

Desserts and Sweets[edit]

- Ti guay/Ti ke (Burmese: တီကေ့; /tìkḛ/, Chinese: 年糕; niángāo) is usually served during the Chinese New Year festival. It is a glutinous rice flour cake made with brown rock sugar or palm sugar. All ingredients are added to the circular mould shape and steamed. It is sweet, chewy and aromatic.

- La mont ( Burmese: လမုန့် ; /la̰mo̰ʊɴ/, Chinese: 月饼; yuèbǐng) is one of the Chinese traditional delicacies enjoyed during the Mid-Autumn Festival. Normally, it has a circular or rectangular shape. The fillings of the moon cake in Myanmar typically consist of lotus seed paste, red bean paste, and sometimes salted egg yolks, providing a rich and sweet flavour.[48]

Vegetarian Dish[edit]

- Stir-fried vegetables (Burmese:အရွက်ကြော်) is a kind of dish that has a balance of saltiness and sweetness, freshness of vegetables—cabbage, cauliflower, carrot, green beans, baby corn, pak choy etc.—are fried with small amount of oil in a wok together with minced garlic. As an additional ingredient, it can also be fried with mushrooms, chilli peppers or egg.

- ^ a b Anusasananan, Linda Lau (2012). The Hakka cookbook: Chinese soul food from around the world. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27328-3.

- ^ Rangoon, Yangon. "19th street in Yangon | Yangon | Myanmar". Yangon Rangoon. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ Zhu, Jingwei; Xu, Yang; Fang, Zhixiang; Shaw, Shih-Lung; Liu, Xingjian (May 2018). "Geographic Prevalence and Mix of Regional Cuisines in Chinese Cities". ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 7 (5): 183. Bibcode:2018IJGI....7..183Z. doi:10.3390/ijgi7050183. ISSN 2220-9964.

- ^ a b Yi-Sein, Chen (1966). "The Chinese in Rangoon during the 18th and 19th Centuries". Artibus Asiae. Supplementum. 23: 107–111. doi:10.2307/1522640. ISSN 1423-0526. JSTOR 1522640.

- ^ Peng, Nian (2021), Peng, Nian (ed.), "Approached to China: Myanmar's China Policy (2016–2020)", International Pressures, Strategic Preference, and Myanmar’s China Policy since 1988, Singapore: Springer, pp. 135–174, doi:10.1007/978-981-15-7816-8_6, ISBN 978-981-15-7816-8, retrieved 2024-05-07

- ^ "Gold Mountain and Beyond: A History of Chinatowns in the United States | National Trust for Historic Preservation". savingplaces.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ Ang, Ien. (2019). Chinatowns and the Rise of China. Modern Asian Studies. 54. 1-27. 10.1017/S0026749X19000179.

- ^ "Stories of Chinatown; Finding the Chinese Spirit in Yangon, Myanmar - iDiscover Maps". i-discoverasia.com. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ Bolesta, A. (2018). Myanmar-China peculiar relationship: Trade, investment and the model of development. Journal of International Studies, 11(2), 23-36. doi:10.14254/2071-8330.2018/11-2/2

- ^ Robert, Claudia Saw Lwin; Pe, Win; Hutton, Wendy (2014-02-04). Food of Myanmar: Authentic Recipes from the Land of the Golden Pagodas. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-1368-8.

- ^ a b Chee-Beng, Tan (2012-08-01). Chinese Food and Foodways in Southeast Asia and Beyond. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-548-4.

- ^ Chen (陈天玺), Tienshi (2022-10-04). "Sino-Burmese Secondary Migration and Identity: Tracing Family Histories". Journal of Chinese Overseas. 18 (2): 358–383. doi:10.1163/17932548-12341471. ISSN 1793-2548.

- ^ "Cultural inheritance of Hakka cuisine: A perspective from tourists' experiences". Journal of Destination Marketing & Management.

- ^ Chen, Mei-Hui; Hsiao, Hsin-Huang Michael; Chang, Yu-Hsin. "The Making of Taiwan Cuisine since 1980s: The Rise of Minnan and Hakka Food". Academia.edu.

- ^ "Kokang: The Backstory".

- ^ "10 Special Yunnan Foods You Need to Try, Famous Dishes".

- ^ Li, Yi (2015). Yunnanese Chinese in Myanmar: Past and Present. ISEAS. ISBN 9789814695145.

- ^ Croddy, Eric (2022), Croddy, Eric (ed.), "Yunnan", China’s Provinces and Populations: A Chronological and Geographical Survey, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 731–753, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-09165-0_33, ISBN 978-3-031-09165-0, retrieved 2024-05-19

- ^ "China's Guangdong Eyes Closer Links with Myanmar".

- ^ "Spicy Chinese mala cuisines booming in Myanmar".

- ^ "Chumkie's Kitchen : Panthey Khauk Swe - Egg Noodles in Rich Chicken Curry Sauce". 11 September 2013.

- ^ "Burmese Panthay Kaukswe Curry". Bit Spicy. 2019-06-21. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ Chumkie (2013-05-30). "Chumkie's Kitchen : Burmese Hsan Pyoke (Congee or Rice Porridge)". Chumkie's Kitchen. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ "San Byoke ( Burmese Congee ) - Burmese Vegan". burmesevegan.com. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ 杨洋. "SE Asia warms up to spicy Chinese cuisine". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ "Spicy Chinese mala cuisines booming in Myanmar-Xinhua". english.news.cn. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ Elaine (2012-10-30). "Mala Dry Hot Pot - Mala Xiang Guo". China Sichuan Food. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ "麻辣香锅". www.xiachufang.com. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ Yi (2023-02-23). "Ma La Mao Cai Recipe". Yi's Sichuan Kitchen. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ a b "What is the difference between "Maocai" and "Malatang"?".

- ^ "Mao Cai". Chinese Food Wiki. 2022-01-04. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ Holliday, Taylor (2020-07-12). "Sichuan-Style Shaokao (Chinese BBQ, 烧烤)". The Mala Market. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ Holliday, Taylor (2020-11-10). "Sichuan Mala Hotpot, From Scratch (Mala Huoguo With Tallow Broth)". The Mala Market. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ "Kyay oh | Traditional Noodle Dish From Myanmar | TasteAtlas". www.tasteatlas.com. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ "Kyay Oh, a New Noodle Soup Shop from Top Burmese, Will Open on January 23". Portland Monthly. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ amcarmen (2021-09-15). "Htamin Gyaw (Burmese-style Fried Rice)". AMCARMEN'S KITCHEN. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ Tha, May Oo (2020-06-25). "Making "kyar san kyaw" Stir-fried Vermicelli". By May Oo. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ^ Su (2017-02-26). "Starchy Gravy Noodle (Kor Yay Khout Swal)". Footprints from Burma. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ "Kung Pao Chicken - HISTORY AND RECIPE". Kung Pao Chicken - HISTORY AND RECIPE. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ Nast, Condé. "Kung Pao Chicken". Epicurious. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ Moey, S. C. (2012-11-27). Chinese Feasts & Festivals: A Cookbook. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0735-9.

- ^ "Dim Sum: Turnip Cake (Lo Bak Go)". Hella Phat Vegan. 2021-12-17. Retrieved 2024-05-05.

- ^ "Chinese Steamed Buns_Suwimon Keeratipibul and Naphatrapi Luangsakul", Handbook of Plant-Based Fermented Food and Beverage Technology (2 ed.), CRC Press, 2012, doi:10.1201/b12055-36, ISBN 978-0-429-10679-8, retrieved 2024-05-19

- ^ Nancy (2020-10-04). "CHINESE TEA LEAF EGGS 茶葉蛋". Nomss.com. Retrieved 2024-05-05.

- ^ a b Leonard, George J. (2012-10-12). The Asian Pacific American Heritage: A Companion to Literature and Arts. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-58017-9.

- ^ "Myanmar Street Food".

- ^ Zhang, Lu; Chen, Xiao Dong (2014-07-11), Zhou, Weibiao; Hui, Y. H.; De Leyn, I.; Pagani, M. A. (eds.), "Bakery Products of China", Bakery Products Science and Technology (1 ed.), Wiley, pp. 673–684, doi:10.1002/9781118792001.ch39, ISBN 978-1-119-96715-6, retrieved 2024-05-19

- ^ "Chinese Mid-Autumn Festival celebrated in Myanmar-Xinhua". english.news.cn. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- Draft articles on food and drink

- Draft articles on Southeast Asia

- AfC submissions on other topics

- Pending AfC submissions

- AfC pending submissions by age/0 days ago

- AfC submissions with the same name as existing articles

- AfC submissions by date/19 May 2024

- AfC submissions by date/08 May 2024

- AfC submissions by date/07 May 2024