Charles Ford (outlaw)

Charles Ford | |

|---|---|

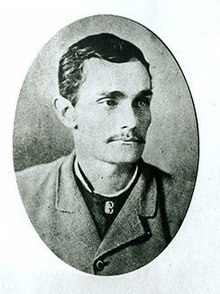

Charley Ford prior to 1884 | |

| Born | Charles Wilson Ford July 9, 1857 |

| Died | May 6, 1884 (aged 26) Richmond, Missouri, U.S. |

| Burial place | Richmond Cemetery |

Charles Wilson Ford (July 9, 1857 – May 6, 1884) was an outlaw, and member of the James Gang.[1] He was the lesser known brother of Robert Ford, the killer of Jesse James.[2][3] Charlie Ford was introduced to Jesse and Frank James by Wood Hite and he joined the gang.[4]

In 1882 Jesse James recruited Robert and Charles Ford to help with a planned robbery of another bank.[5] Thomas T. Crittenden offered $10,000 for the capture of Jesse James, and on April 3, 1882, Robert Ford shot Jesse James.[5] He and Charles Ford were convicted and were sentenced to be hanged, but were pardoned by Crittenden.[5]

Afterwards, Charles heard a rumor that Frank James was searching for both with plans of mortal revenge.[6] Two years later, after a period of deep depression following James' death, terminal illness from tuberculosis, and a debilitating morphine addiction, Charles Ford died by suicide on May 6, 1884.[5][7][8][9]

The Murder of James[edit]

Inside a house at 1318 Lafayette St. in St. Joseph, Missouri, was a one-story white wood cottage with green shutters, sitting on a hill overlooking the town on Monday, April 3, 1882, rented by Thomas Howard. He was reading a newspaper article about the surrender of Jesse James Gang member Dick Liddil to Missouri authorities. “Liddil was a traitor and ought to be hanged”, he said. After breakfast, Mr. Howard and Charlie Ford went to a stable behind the house to tend to the horses. As they returned to the house they entered the living room and began taking off their outerwear and commenting about the unusually warm weather. Howard stated, “I guess I will take off my pistols”.[10] He then picked up a feather duster and stepped onto a chair to clean some pictures on the wall. Bob and Charlie sneakily moved between Howard and his guns, Charlie giving a wink to Bob signaling him about their plan they had previously arranged. Both drew revolvers on the man on the chair, now with his back turned. Hearing the click of a weapon being cocked, Howard started to turn his head, but was instantly shot down by Bob. The sound echoed throughout the whole house. Charlie never ended up firing his revolver, and instead lowered his gun as the man fell to the floor, with a bullet in his skull.[11] After hearing the sound, Howard’s wife rushed into the room, and the brothers tried to explain that the gun had only accidentally gone off and by chance hit Howard. Except Howard’s wife was hesitant to believe the two, as it seemed impossible. The Ford brothers then dashed to the telegraph office down the way and sent messages to Clay County Sheriff Henry Timberlake, Kansas City Police Commissioner Henry H. Craig and Missouri Gov. Thomas Crittenden. Next, they used a telephone to call the office of City Marshal Enos Craig. Thomas Howard, the man they had killed, had earlier used the alias John Davis “Dave” Howard, among others., but the two discovered his real name was Jesse James.[12] [13]

Relationship to Jesse James[edit]

The Ford brothers initially began relations with outlaw Jesse James in the summer of 1879. Jesse had been living in Tennessee since 1877, trying to live a more honest life and make a more honest living following his disastrous attempt to rob the Bank of Northfield, Missouri, the year before. Jesse suffered from Malaria making it hard for him to transition from a criminal lifestyle to an honest living. This being said he returned to Missouri to put together a new and “fresh” gang, which is where he “luckily” crossed paths with Fords. James T. and John Ford, the father and brother of Bob and Charlie. [13] Members of the gang included Ed Miller, a new recruit. The exact details are unclear, but it seems that at the time that Ed wanted to leave the gang, Jesse felt as if he would be betrayed and shot Miller, resulting in his death. Jesse then lied telling Charlie Ford that Ed had become ill and had gone down to Hot Springs, Arkansas. Then came Jim Cummins, a former guerrilla comrade of Jesse’s. Jim’s sister Artella had married Bill Ford, who was the uncle of Bob and Charlie. Cummins became suspicious that something bad had happened and tried to locate Miller. It was apparent that Jesse’s choice of gang members exemplified his depravity and unfortunate situation.[13] [14]

Charles Ford and Theater Touring[edit]

The Ford’s careers were among the most law-abiding relative to most outlaws at the time; even if their story in the papers is displayed through the lens of a general villainy. Research into their lives after the assassination revealed the brothers' successful side-hustle show business beginning in the 1880s around the rise of show business. They had a goal to promote their story, specifically the assassination, through their performances. From the papers, October 1882 - “Dear sir — Your act was one which could only have been accomplished by a man of courage. You have rid the world of a human tiger. What hunter would have thrust himself in the lair of a tiger with a tigress and young. You saved the country from a terror that preyed with artful devilry upon defenseless man and woman. … I take pleasure in calling you my friend. Miss — — ” From the perspective of the newspapers written at the time, it was apparent that the Ford Brothers were generally not very popular with the public and often assumed to be useless outlaws. Yet, the Ford’s began performing, as live theater was gaining more and more fame out in the Wild West and museums began advertising hourly exhibitions all over the country in hundreds of cities. In the months following Bob Ford’s assassination of Jesse James, Bob and Charley went on a live theater tour, showing their assassination for audiences in places like Brooklyn, Chicago, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and Arkansas and cities all across the United States. Bad publicity was evidently good for the Fords, as they sold out crowds in some of the largest cities in the country. Their performances became regular at towns all across America often identified by an entrance sign stating, in drippy red paint, the words “The Ford Boys: Slayers of Jesse James”. [15] [16] Due to this increased public image and more advertisement of the brothers, the Fords were stirring up publicity. Specifically, the Ford Brothers could be found performing a reenactment of the assassination in a Kansas City variety show. In the weeks and months ahead, newspapers often printed shameful accounts of the Fords; “The Ford boys … are not a pleasant pair to look on; one is a thin face looking scoundrel, whose black eyes are constantly on watch, as if a spectre is at his back”. From a newspaper in Massachusetts, “The Ford Boys endeavored to clean out a whole audience in Boston, because someone volunteered they were no good, and were only quieted by the arrival of the police. The prejudice against the boys all came out of a refusal on their part to eat baked beans”! Chicago, Sept 1, 1882 — Bob Ford, who slew Jesse James in St. Joseph last spring, was arrested on State Street this morning … For the past two weeks both of the Ford boys have been in this city playing at the cheap theater on State Street in a blood and thunder drama. They have … (been) … looking for notoriety and running with fast women of the town and frequenting the cheap variety saloons.

A decade after he shot Jesse James, thirty-year-old Bob Ford was assassinated at his bar in Creede, Colorado. Edward O’Kelly, who committed the murder, never gave a motive for the crime. But Charles Ford continued touring for a while after the death of his brother, even though his brother played a larger part in the literal assassination.

Life After Assasination[edit]

Outlaw, and member of the James Gang. He was the lesser known brother of Robert Ford, that “dirty little coward” who killed Jesse James on April 3, 1882. Charles was also involved in the conspiracy to kill James. r. Charlie was the one with stronger ties to Jesse, having participated in the Blue Cut train holdup in 1881.. It was to be the last train robbery of the James Gang, netting the six members some $3,000 in cash and jewelry taken from the passengers. Also participating in the robbery were Frank and Jesse James, Dick Liddel, and brothers Clarence and Wood Hite. Charged with first-degree murder, Charlie was sentenced to hang but was quickly pardoned by the governor of Missouri. Afterward, Charlie heard a rumor that Frank James was searching for both him and his brother, with plans of deadly revenge. Charlie moved from town to town for the next two years, changing his name several times. When word of the shooting reached authorities, Ford was arrested, but when he informed detectives that he had access to the much-wanted Jesse James, he was released. Next, Ford secretly met with Missouri Governor Thomas T. Crittenden, who told him that if he killed the notorious outlaw, he would receive a full pardon for the Hite murder and the killing of James and the reward money. Ford agreed to perform the deed and next met with the Sheriff of Clay County, where the two formulated a plan to get Jesse James.

Death[edit]

But assassinating the outlaw had a huge emotional impact on Charlie. He grew paranoid and depressed, fearful that Frank James or a Jesse fan would kill him. Experienced a period of deep depression following James' murder and terminally ill from tuberculosis and a debilitating morphine addiction, ultimately Charles Ford committed suicide on May 6, 1884. [16] [18] [13]

Family and Relatives[edit]

Charles Ford was one of the eleven Ford children born to James Thomas Ford and Mary Ann Bruin: Sarah J. Ford (b. abt. 1841) Georgiana Ford (b. abt. 1843) Mary T. Ford (b. abt. 1845) John Thomas Ford (b: November 6, 1847) Martha Elizabeth Ford (b: April 22, 1849) Harriet Ford (b. abt. 1851) Elias Capline Ford (b: July 10, 1853) Amanda Francis Ford (b: April 1, 1855) Charles Wilson Ford (b: July 9, 1857) Wilber Pottuck Ford (b: November 19, 1859) Robert Newton Ford (b: January 31, 1862)

In popular culture[edit]

- Charles Tannen portrayed Charles Ford in Jesse James (1939) and The Return of Frank James (1940).

- Tommy Noonan portrayed Charles Ford in I Shot Jesse James (1949) and The Return of Jesse James (1950).

- Louis Jean Heydt portrayed Charles Ford in The Great Missouri Raid (1951).

- Paul Frees portrayed Charles Ford on the CBS radio show Crime Classics on July 20, 1953 in the episode entitled The Death of a Picture Hanger.

- Frank Gorshin portrayed Charles Ford in The True Story of Jesse James (1957).[19]

- Christopher Guest portrayed Charles Ford in The Long Riders (1980).[20]

- Alexis Arquette portrayed Charles Ford in Frank & Jesse (1994).[21]

- Sam Rockwell portrayed Charles Ford in The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007), based on the novel by Ron Hansen.[22]

- Alex Rose portrayed Charles Ford in the Timeless episode, The Murder of Jesse James (2017).

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Beights, Ronald H. (2005). Jesse James and the First Missouri Train Robbery. Gretna: Pelican Publishing. p. 171. ISBN 9781455606658.

- ^ Stiles, T. J. (2002). Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War. A.A. Knopf. pp. 363–375. ISBN 0-375-40583-6.

- ^ Yeatman, Ted P. (2000). Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend. Cumberland House. pp. 264–269. ISBN 1-58182-325-8.

- ^ McCoy, Max (October 14, 2016). Jesse: A Novel of the Outlaw Jesse James. Speaking Volumes. p. 190. ISBN 9781628155334.

- ^ a b c d Miller, Wilbur R. (June 19, 2012). The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America: A-De. SAGE Publications. p. 874. ISBN 9781412988766.

- ^ "The Complete List of Old West Outlaws - Last Name Begins with E-G". Legends of America. Archived from the original on October 17, 2008. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Mault, Deena (February 27, 2006). "[Ford] Robert and Charles Ford ancestors". RootsWeb. Ancestry.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ "Charlie Ford's Funeral". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. May 8, 1884.

- ^ "Suicide of Charles Ford". New York Times. May 7, 1884. p. 5. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- ^ Yeatman, Ted P. "Jesse James' Assassination and the Ford Boys". History Net. History Net LLC. Retrieved 9/17/2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help); More than one of|author1=and|last1=specified (help) - ^ Yeatman, Ted P. "Jesse James' Assassination and the Ford Boys". History Net. History Net LLC. Retrieved 9/17/2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help); More than one of|author1=and|last1=specified (help) - ^ Yeatman, Ted P. "Jesse James' Assassination and the Ford Boys". History Net. History Net LLC. Retrieved 9/17/2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help); More than one of|author1=and|last1=specified (help) - ^ a b c d e Hardin, Jerrad. "The Ford Boys: 140 Years of Tourism". Medium. Medium. Retrieved 08/02/23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help); More than one of|author1=and|last1=specified (help) - ^ Joshi, Siddhesh. "Charles Ford (outlaw)". Alchetron. Retrieved 11/06/23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ^ Boardman, Mark. "The Other Assassin". True West: History of the American Frontier. Retrieved 04/12/19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help); More than one of|author1=and|last1=specified (help) - ^ a b Griffith, John. "Charlie Ford(1857-1884)". Find a Grave. Retrieved 08/05/1999.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ^ Alexander, Kathy. "Old West Outlaw List". Legends of America. Legends of America. Retrieved 12/21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ^ "Charles Ford (outlaw)". en-academic. Retrieved 11/29/08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ^ Braudy, Leo (2002). "Westerns and the Myth of the Past". The World in a Frame: What We See in Films (25th Anniversary ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 138. ISBN 9780226071565.

- ^ Pallot, James (1995). The Movie Guide. Berkeley Publishing Group. p. 493. ISBN 9780399519147.

- ^ Craddock, Jim (2006). Videohound's Golden Movie Retriever. Cengage Gale. p. 333. ISBN 9780787689803.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (September 21, 2007). "Good, Bad or Ugly: A Legend Shrouded in Gunsmoke Remains Hazy". The New York Times. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- 1857 births

- 1884 deaths

- 1880s suicides

- James–Younger Gang

- Suicides by firearm in Missouri

- American Old West stubs

- American people stubs

- American people convicted of murder

- American prisoners sentenced to death

- People convicted of murder by Missouri

- Prisoners sentenced to death by Missouri

- Recipients of American gubernatorial pardons